Broadsnark's "The Power of Principle" is an excellent description of the trade between having principles and having power. If you haven't read it already, it's well worth reading.

I agree with that, but it's a strongly-debated point. After all, if the current government is doing lots of bad things, wouldn't it be good to have someone even slightly better in? The lesser of two evils, as the cliché goes. So why doesn't sacrificing principle for power work?

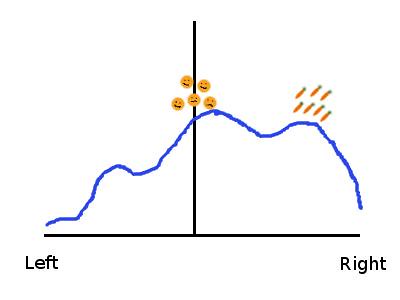

Here's my theory as to why things work out that way, with diagrams.

Some simplifications, and why they're okay

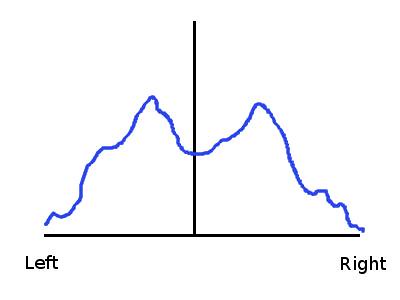

Okay, so let's start by making a big simplification: we'll just consider one political issue, and assume that it's one that strongly influences people's votes. In practice, the effect below tends to happen to lots of policies together, so it's not an important simplification - when you consider every issue at once, the same thing happens. The members of the electorate then have various opinions about what the solution to this issue looks like, which are distributed in some sort of distribution.

I've drawn this with "left" and "right" because I think the diagram is more readable that way than with "up" and "down". There's not necessarily any connection on this issue with the traditional left-wing and right-wing positions, though, and the argument I'm making will generalise to issues where the options can't be expressed on a linear scale1, or indeed in Euclidean geometry.

Exactly what the distribution looks like doesn't really matter. There are usually going to be more people around the middle than at the edges, and it's not going to be completely smooth - there'll be peaks here and there that represent popular solutions.

Let's also assume that in general people vote for political parties close to their own opinions where possible. There's plenty of room for misinformation about who actually supports what policy to creep in, but since both sides are trying it the net effect is going to be relatively minor.

Let's also assume a 2-party system with a non-proportional2 electoral system that makes it very hard for a third party to break in anywhere, as we have in the UK (even with the rise of the Lib Dems) or in the USA. This is a fair assumption because it's what we have.

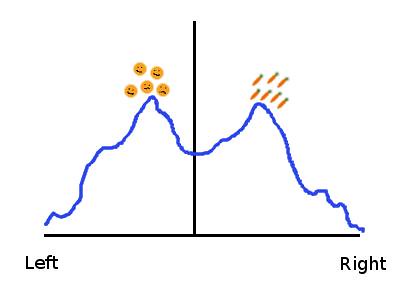

So, next picture: two of the big peaks of opinion distribution near the centre are occupied by the major political parties - the Oranges and the Carrots.

Diagram 2: Same as the first, but with the Orange party occupying the peak to the left of the centre, and the Carrot party occupying the peak to the right of it.

There's then a general election. The Orange party loses the election, and the Carrots party enters government.

Why running to the centre works in the short-term

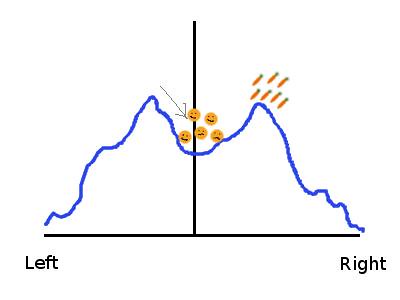

This is the point where the "principles or power" argument comes in to play. Obviously, it's really bad for the Carrot party to be in power. There's no real hope of another party coming out of nowhere to save the day, at least not by next election, so to get the Carrots out, the Oranges have to get in. But the electorate has just been presented with the Oranges, and didn't like them - it preferred the Carrot policies3.

So, to "be more electable", the Oranges move their policy along a bit towards the centre.

Diagram 3: The Carrot party is still on the right peak, but the Oranges have moved their position into the valley between the two peaks.

At the next election, the centre point between the Orange policy and the Carrot policy is in a different place. The key swing voters in between the two parties are now going to cast their votes a bit differently, with the Oranges picking up more of their votes than before. They might lose a few votes from the left-most end of the distribution, too, but they can afford to: votes they lose from the left go to an inconsequential rival or abstentions. Votes they take from the right come off their major opponent's totals. They can afford to lose almost twice as many votes from the left as they gain from the right and still come out ahead.

For instance, if there are 100 voters in all, and 53 voted Carrot and 47 voted Orange, then by convincing 10 Carrot voters to vote Orange, the scores become 43-57. A 6 vote margin has been changed to a 14 vote margin in the other direction. If Orange loses 12 voters from their left as a result, they're still 2 votes ahead of the Carrots at 43-45, despite losing more voters than they gained.

So, by following this strategy, the Oranges are able to regain power at the next election.

So why doesn't everyone just end up in the centre?

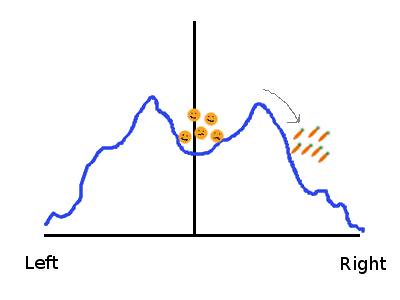

Over in a formerly-smoke-filled but now nicely air-conditioned room at Carrot Headquarters, the party green-wigs need to decide on a strategy. They have two choices.

- They can do what the Oranges did to them, and move closer to the centre, to try to retake power. There's not a lot of spare space to move into, though, without dropping this as an election issue at all, which won't actually do them much good. And you need to have some space to manouevre for the 2:1 multiplier you get from winning swing voters to actually be possible.

- They can take a longer-term view, and move their own position to the right. That's probably closer to where they wanted it to be anyway, before an earlier pragmatic Carrot leader decided that on top of the peak was a good place to be.

Diagram 4: The Carrot party has also moved off its peak to the right, re-opening a wider gap between the two parties.

The Carrots pick option 2, and lose the next election too. There's probably some internal squabbles at this point, but they wait them out.

... and then, the plan pays off.

Because public opinion is not static. It's fluid, and on some issues it can change really quickly in the right circumstances. Like advertising, if you say something for long enough to enough people, some of them will listen, and change their minds. If a party states a particular policy, its supporters become more likely to support that policy.

Consider, for instance, at this YouGov poll (PDF) from December. On page 7, there's a question about whether short prison sentences or community sentences are more effective.

In general, imprisonment is the stereotypical Conservative policy. They have the reputation for being "tougher on crime". So it was in some ways an unexpected announcement of Conservative policy that they would want to go for community sentences. In the poll, though, Conservative voters split 36:44 in favour of community sentences.

Perhaps the stereotypes are wrong? Public opinion often isn't what it's claimed to be. Are the Conservatives playing to their base after all?

This time, though, there's something else at work: compare that poll to this other poll (PDF), also carried out by YouGov, only a month earlier.

In this poll, Conservative voters are split 57:35 against the use of community sentences. In a month, there has been a 30 point swing in Conservative voter opinion. Additionally, there has been a 19 point swing in general voter opinion (which includes the Conservatives). From being a policy that had the weight of public opinion against it - and think tanks warning the government away from it - it's now one that the public is roughly split on.

There are differences of question wording between the two polls, but these mainly consist of the later poll having a tiny neutral summary of the purported advantages of each choice (which I don't think is particularly significant), and the later poll attributing the community sentences policy to the current government (which may well be a significant wording difference, but one that strengthens my point if it is)

I don't think public opinion is quite that fluid on most issues - sentencing policy is in general not an issue of major importance to most voters - and in general that sort of change takes years or decades rather than weeks, but it definitely happens over time.

So, how does this affect the diagram?

Diagram 5: The distribution of public opinion has shifted, with the peaks moved towards the parties' new positions.

The next election, the Carrots win it, by about the same margin as they won the election back in Diagram 1.

So, the Oranges have to do something. It worked last time, so they move their policy off the peak, and closer to the Carrots.

After a couple of cycles of this, what happens is of course that the Oranges have ended up fairly close to where the Carrots were originally. At this point, the Carrots can start moving slowly back towards the Oranges, both picking up votes themselves, and trying to make the new consensus one that sticks so that they don't have to defend it in future. The result: the Carrots have spent a fair proportion of the time in power, the Oranges will be implementing their policies anyway while the Carrots are out of power, and the Carrots can direct their energies to winning the next argument.

It took a little more than a single election cycle, but the Carrots have most definitely - by sticking to their principles - won. This is why, as Broadsnark said:

The people whose power lasts are those whose power comes from their principles, not from selling their principles out. It’s not naive to think that people shouldn’t sell their principles to power. It’s naive to think that someone in power who has sold their principles can do us any good.

So, the Oranges have power - and are using it to implement Carrot policy. Whether they count this as a success depends entirely on whether they went into politics to get power or to advance their principles. Meanwhile, the people who liked the Oranges' initial policy are stuck out on their own, without any formal representation, and now have to work hard to draw the Oranges (and ideally the Carrots, too) back towards them.

I've given this example with political parties, but it really works for anyone trying to make a difference to anything - in the long term, the successful people are people who've convinced opinion to follow them.

What if the Carrots are really bad?

Some governments are so bad that even letting them be in power for one term is going to be disastrous, and it's worth paying a high price to keep them out. The problem with this argument is that you can't keep them out forever.

Governments in the UK lose an average of 3 points of popular vote between elections. Virtually none have actually gained popularity between elections. Sooner or later, the accumulated frustrations of the population are going to kick them out no matter how well they're doing.

The opposition will be back in power eventually and you can't stop this. It's not worth delaying it a few years if the cost is implementing their policies anyway.

There are in a democracy ways other than being the official opposition to make it politically unviable for the government to do something, anyway.

(This only applies if you trust the opposition to hold another fair election, of course, but if you don't there are bigger problems)

Wouldn't this just lead to no-one compromising on anything, and nothing getting done?

Maybe.

In practice, though, no. There's a major difference between compromising on what gets implemented now, and compromising on your underlying principles.

To illustrate this, say there are two issues (A and B), with three possible policies (A0, A1 and A2, with A1 being 'between' the other two policies, and similarly for B).

If A2 is the current situation, a supporter of A0 could team up and compromise with supporters of A1 to get A1. It's not what they actually want, but it's closer to it. And if between them they can make A1 stick, then maybe in a few years it'll be possible to get mass support for moving to A0.

This is a good compromise, and isn't inconsistent with having principles and keeping them.

Suppose, then, that this support of A0 also supports B0. The current situation is A1 and B1. A supporter of A2 and B0 offers to help with getting B0 in exchange for help in getting A2.

Assuming that A and B are both major issues - if A is "who pays for lunch?" and B is "should we invade Norway?", this doesn't hold - this is a bad compromise. To take it, the principle of A0 will have to be sacrificed.

In between the two is an offer to support B0 if you don't campaign for A0 and accept A1 as sufficient (assuming A1 is currently true) - at least in public.

I think this is still generally a bad deal - both sides of the deal want (or at least, aren't opposed to) B0 already. So you could probably get B0 another way without giving up the possibility of A0. There might be cases where it's worth taking, though, if B0 is likely to be the sticky position, and so you can go back to working towards A0 relatively quickly once B0 is done.

The reason that the good compromises are good is that they don't stop you working on moving mass opinion towards your position. The reason the bad compromises are bad is that you have to shut up and contribute towards making things worse, which means that when you decide you've had enough, you've been digging your own hole for the last few years and have to fill that in first.

Only making good compromises means that political alliances on one issue aren't necessarily going to be the same as the political alliances on a different issue. There's nothing wrong with that, either, though it can take some getting used to.

Conclusion

The way to win, in the long-term, is to have principles, to stick to them, and to argue for them consistently and convincingly. There are plenty of situations where the short-term gain is from abandoning some principles to help others: beware.

Having short-term political power, in the way the default thinks of "political" and "power" is not necessarily useful, and may in some cases be actively counter-productive to principled success because the costs of getting it are too high.

Footnotes

1 If I was better at drawing, there would be a picture of an opinion surface in two dimensions to demonstrate this. Please imagine your own.

2 In a proportional system, the incentives are different, and the advantages to sticking to your principles are much clearer. It's the main reason that I want one.

3 Not necessarily true in a non-proportional system, but let's assume that like the UK and USA, the tendency is to expand differences in the popular vote, rather than reduce them. Elections where the winner of the most seats and the winner of the popular vote differ will result in a very different - and generally messier - political dynamic anyway.